Cynthia’s Top Ten Films of 2022

“I think it realized that it was time to let go.”

If 2021 was the year that brought the return of cinemas, then 2022 was the return of cinemas being a social experience, at least for me. Despite the reopening of cinemas, in 2021 I still felt isolated from my fellow moviegoers as I sat with my mask on and deliberately made sure that I was at least three seats away from the closest human being. That, or finding myself alone in the theater with no other attendees.

2022 provided a feeling of normalcy in the congregation of the movie hall. I found myself less alone in the theater, with more packed screenings and livelier audiences, to the point where I finally experienced sitting in the overflow balcony of my local theater for an exciting screening of Chunking Express. It was a year where collectively and loudly sobbing to a mother-daughter or father-daughter relationship felt comforting rather than isolating. Children screaming the words “Banana!” at a filled Minions screening felt innocently pure rather than intensely grating. Fist-pumping and hollering at a crocodile eating someone up or a rope ripping a limb off of a hunter felt exciting rather than out of place. Hell, a screening of Top Gun: Maverick four months after its initial release somehow remained packed to the brim in the closing days of summer, complete with a woman in front of me gasping at the chiseled bodies playing football on the beach. If 2022 was just a preview of the electricity that could be felt in the theater again as a social experience, then bring on 2023!

—

Honorable Mentions

Avatar: The Way of Water (James Cameron), The Fabelmans (Steven Spielberg), Banshees of Inisherin (Martin McDonagh), After Yang (Kogonada), and No Bears (Jafar Panahi)

—

bonus

Irma Vep (2022)

I would be remiss to not at least mention Olivier Assayas’s 2022 release of Irma Vep on this list, despite its advertisement as a television miniseries (one character in the series may disagree). An episodic reflection of his 1996 masterpiece of the same name, Irma Vep continues the same exercise Assayas found himself in 1996 where he examined the state of cinema, only this time through Mira (Alicia Vikander), an actress who attempts to be the newest muse of fictional director Rene Vidal’s (Vincent Macgaine) as he attempts to remake his own remake of Les Vampires.

In this new landscape of cinema, Assayas’s existentialist quandaries become all the more dizzyingly beautiful. Superheroes being hilariously perverted inspirations for costume design in the original become corrupted and claustrophobic. Queerness is more fluid and free, while creativity, in the face of intense commodification, is less so. Away from the chaotic 20th century of his youth, Assayas works from a wiser state, adding more reflections about himself as a creative while remaining scathing to the industry around him. In its extended runtime, Irma Vep becomes a purging of mistakes and anxieties, a reflection of cinema’s history, an emotional projection of the power in desire, a visualization of the blurring of fact and fiction, a wiser yet oddly sappy view on the relationship of art and reality, an exercise of absorbing and letting go, and a very pretentious but equally hilarious examination of creativity in capitalism’s current form. Although nothing can hold a flame to his original masterpiece, Assayas's earnest attempt to decode the cinematic world around him unfolds into a charming appreciation of the process of creating cinema and an honest reclamation of its purity.

—

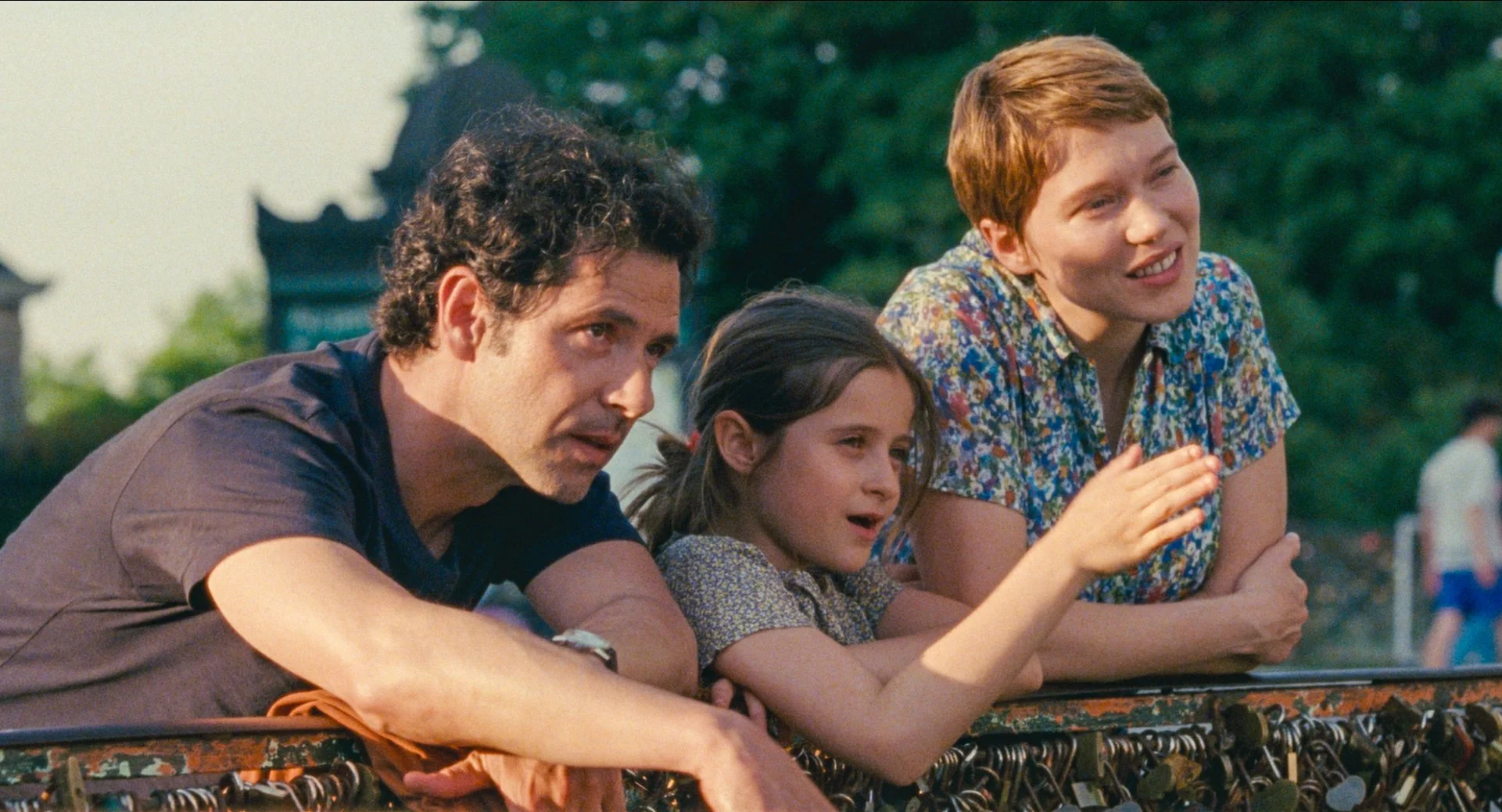

10. One Fine Morning

Mia Hansen Løve is no stranger to the entanglements life throws at us, delivering films where loose ends remain untied and character motivations come more from the impulse of the heart rather than the logic of the mind. In One Fine Morning, Løve finds herself back in familiar territory. Sandra’s (Lea Seydoux) life is in a state of flux. Her father Georg (Pascal Gregorry) suffers from memory loss while her love life finds a new spark in Clement (Melvil Poupad), who is a married man. As one relationship blossoms for Sandra, bringing the excitement and thrills a new love often presents, a longstanding familial relationship slowly concludes.

Juggling the lives around Sandra, Løve acutely balances the tension of something new against something old, examining the progression of time in an individual’s life and how it compares to friends and family members whose own timelines are different than your own. Devastating lines about objects and their lingering identities emphasize how regret shrouds grief. A lingering camera on a bus ride home capture the potency of a simple text. Small gestures like these pinpoint the complexities of simply living while watching time pass by. Through these observations, Løve produces a landscape that feels lived-in in their minute details, while at the same time, finding resilience and a sense of quaint relatability while trying to maneuver the different tenses of life that external forces present. In doing so, Løve’s delicate portrayal of a woman amid everyday struggles presents a uniquely courageous and beautiful view on life, even in its monotony.

—

9. Top Gun: Maverick

The blockbuster in the 21st century has reached its tipping point. Well-executed cliches sacrifice themselves for meme-able cameos. Nostalgia is now a cloying mechanism only designed to sentimentalize audiences. And green screens create visuals that are more headache-inducing than they are coherent. In this respect, Top Gun: Maverick and Tom Cruise’s never-ending death wish is a breath of fresh air that brings renewed life to the blockbuster.

Never steeped with too much nostalgia or superfluous minutia, Top Gun: Maverick returns to the basics with a structure that is simple yet effective. Its character drama, built from the ghosts of the past, is deftly conveyed by an unexpectedly reflexive turn by Cruise and an angsty Miles Teller. Its score is interlaced with the cheesiest Lady Gaga banger that will never fail to make me shed tears. Combined with the cinematic and practical flourishes of Tom Cruise actually hitting high speeds — all with an incredibly rigid precision by director Joseph Kosinski — Top Gun: Maverick finds the right balance between the cliche and the spectacle to craft the perfect blockbuster. Even though this is still very much an overwrought piece of U.S. military propaganda (the nondescript enemy with uranium clearly alluding to Iran is comical), Top Gun: Maverick has a filmic appreciation for the tried-and-true structure of a 80s blockbuster that, pardon the horrible pun, did take my breath away.

You can read Cinema As We Know It's review of the film here.

—

8. All the Beauty and the Bloodshed

“All the Beauty and the Bloodshed”. Utter those words aloud and feel the emotional resonance fill the air. Now attach them to a film, and watch how Laura Poitras’s stunning documentary lives up to the potency of its title and then some. Focusing on photographer and activist Nan Goldin, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed beautifully captures Goldin’s sprawling life with a warm intimacy as we watch her come to staggering revelations about her own identity, revelations she openly admits are the first time she has said aloud. Despite this confessional-like premise, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed does not reduce to a simple diary entry. Rather, it develops into a personal collaboration between its subject and director. Interlacing archival material with Goldin’s own vivid slideshows and portraitures, we see how much of Goldin's intimate life, with all its joy and pain, has been provided for us to bear witness to, making the collaboration feel like both a profile of someone’s life and a powerful act of self-autonomy.

And so, when we learn what “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” mean within the context of the film, one can only be shaken by what Goldin has had to endure throughout her lifetime. We realize that every single point of her life, and the art she has created in response, have always built upon each other to be political and rebellious. Taking pictures, documenting pain, celebrating queer joy, and simply having the will to survive: that is activism. In some fucked-up way, with all Goldin has had to endure, Goldin was born to engage and reflect on every moment she found herself in, and the film's willingness to shed all the layers of Goldin’s life is the key to beautifully demonstrating this fact. To still have the autonomy to reveal one’s soul and expose the light and suffering that comes along with it, in the name of personal necessity, reckoning, and political defiance, especially within the context of Nan Goldin’s activism and art, is one of the most mesmerizing and emotionally potent things to bear witness to.

—

7. Showing Up

Kelly Reichardt’s ability to render the mundane as something inspired adds new layers of anxiety and comedy with her latest feature Showing Up. This time her shifted focal point centers on the art world, specifically, an artist in flux. Libby, played by the wonderfully dry and self-serious Michelle Williams, finds herself up against a self-imposed deadline for her first-ever art show. While dedicated to finishing her art, Libby’s life outside her discipline does not share that same dedication. Her colleague and landlord, Jo, played by Hong Chau with a hilariously self-involved performance, will not fix the hot water. To make matters worse for Libby's self-esteem, Jo is working on not one, but TWO art shows. Combined with a job at the local art school she would rather neglect and a family experiencing a myriad of issues, Libby finds herself in a state of disarray.

The narrative is the closest thing to slapstick we’ve seen thus far from Reichardt, albeit with the driest of humor. Yet, what makes Showing Up so effective is its observational self-reflexivity, acutely attuned to both understanding how ridiculous it can feel to create art and ascribe a higher meaning to it, while at the same time acknowledging how meaningful and necessary it is; feelings of imposter syndrome can feel so heavy, but a moment of creative inspiration can make the world feel controllable. In the grander scheme of life, and in comparison to things like a family member's health, these moments within art can feel a bit silly. By inspecting an artist’s relationship with their craft and juxtaposing it with harsher realities, Reichardt provides a fully realized world tinted with the beats of sadness, hope, and all the contradictions in between. In doing so, Reichardt makes the heart both swell and dip while providing a melancholic optimism toward the necessity of art.

—

6. The Eternal Daughter

The Souvenir and The Souvenir Part II were both auto-fictional memoirs that pierced the heart. Layered with grief, artistry, and self-reflection, those films reckoned with director Joanna Hogg’s past via her character Julie (Honor Swinton Byrne). However, one of the more poignant sequences away from Julie in those films are the lingering shots of Julie’s mother, Rosalind (Tilda Swinton), alone, doting on her daughter. Those isolating frames told a thousand stories regarding loneliness, and in Hogg’s latest, The Eternal Daughter, she attempts to expand upon them.

Shifting her storytelling roots to an older Julie, now played by Tilda Swinton, and within the constructs of a ghost story, The Eternal Daughter follows mother and daughter as they venture for a holiday in an old family estate-turned-hotel. A once-conceived space of delightful memories now feels vacant and mysterious as both mother and daughter find themselves to be the only guests checked in. Precise howls of the wind and dramatic window slams fill the sonic landscape while long hallways, dark kitchens, and fog-filled exteriors build an ominous atmosphere. As Julie attempts to locate these noises that prevent her from falling asleep, she confronts her storytelling abilities as an artist. In one scene, Julie secretively records her mother’s dictated memories, questioning whether this is an act of preservation for what she may soon lose or an exploitative venture to create a new film and feel inspired again. These past memories pose the question whether new revelations are disorientations of what we once knew or a lapse in fully understanding the people we love. What began as a ghost story slowly unfolds into an exploration of grief and loneliness that also happens to examine the merit of stories we get to tell ourselves and others. Taken together, it’s an enamoring film that’s both haunting and mystical.

—

5. TÁR

Subscribing to the idea that TÁR is about “cancel” culture simplifies what TÁR is really about. Sixteen years since Little Children, a darkly comedic examination of suburbia, it is hard to imagine director Todd Field simplifying his worldview into something as nonexistent as cancel culture. Rather, and to our benefit, Field creates a complex study of egoism, power, and control and their intersection with art and passion.

Following fictional composer Lydia Tár, played dynamically by Cate Blanchett, we observe a prodigious maestro who slowly descends into free fall from her grandiose desires for myth-making. At a rigorous 157 minutes, Field creates a masterwork of bravado falling to the wayside. In Blanchett’s performance, we see a figure who is simultaneously horrible yet warmly rootable and deeply vulnerable. In Field’s script, we engage with a dark comedy that slightly sneers at the pretentiousness of art community while, in a metatextual sense, still playing in the molds of it by simply creating this film. In Noemie Merlant’s mousy performance mouthing a long-winded expository dump, we see the cracks that foreshadow the chokehold precision in which Lydia Tár expects her life to be.

The blinding desire to be in total control of time. The difficulty to escape the confines of the rigid rules of a homogenous society. The desperate need for myth-making. The interrogation of the power structures and values that perpetuate and keep these people afloat. The questioning of our complicity in this system as we reckon with our reverence for Lydia Tár, an objectionably horrible person. The audacity to float all these ideas and leave us with more questions than answers makes TÁR exhilarating. If all falls from grace executed similarly, I would never look away.

—

4. Everything Everywhere All At Once

Everything Everywhere All at Once is one of the few films living up to its name. From butt plugs to sausage fingers to talking googly-eyed rocks, Everything Everywhere All at Once is as juvenile as its contents suggest. Throw in a multi-verse storyline, and you would think you were watching a poor attempt at a Marvel film. Yet, despite director Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert’s (the Daniels) throw-everything-at-the-wall-and-see-if-it-stick approach, Everything Everywhere All at Once works, miraculously rendering its zaniness into a thoughtful and kind emotional reckoning of immigrant assimilation, regret, and second-generational immigrant trauma.

In its simplest terms, Everything Everywhere All at Once is a film about Chinese immigrant Evelyn Wang, Michelle Yeoh, with a stoic yet vulnerable performance, as she faces the impending doom of having to file her taxes for her less-than-successful laundromat. What begins as a dreaded day at the IRS turns into a multi-verse adventure caper involving a fanny-pack-focused wuxia, a Pixar-inspired rivalry, and a whirlwind romance, to name a few, resulting in a plain-old fun visual feast.

Well-executed fights are visibly precise and exciting. One-second cuts have the emotional potency and catharsis of a much-need scream. And glowing magical breakfast foods bear the weight of 21st-century millennial dread. But within its freneticism, there’s the understanding for moments to breathe, moments of levity that become kernels of truth. These quiet pockets feel like everything. And, when we finally land back on our feet, the Daniels extend their empathetic hand, giving us the grace of knowing that whatever will come our way, there is beauty in living in the now because, even at its worst, it truly is the best that we have.

You can read Cinema As We Know It's review of the film here.

—

3. Decision to Leave

And so the lyrics go, “When I think of something, it's a past memory, still yearning for it. Where did that person go, lonely in the fog, I go endlessly.” This swooning lick from the famous Korean song “The Mist” coincidentally happens to be the favorite song of Decision to Leave’s central murder suspect Song Seo-Rae (Tang Wei). Director Park Chan Wook uses these lyrics to a beguiling effect, turning a murder mystery into a swooning romance fueled by mysterious and hazy longing. Assigned what seems like a closed murder case, detective Hae-Joon (Park Hae-il) finds himself entangled with his obsessions and yearnings after meeting Seo-Rae, the murder victim’s wife-turned-suspect. What follows is a sensual romance that plays similarly to a surreal dream as Park’s visual dynamism invokes a woozy and aching atmosphere of yearning.

Simple stakeouts become a visual literalization of the desire for human connection as the screen transplants Hae-Joon to appear in the very room he is staking out. Interrogation sequences turn into a kaleidoscopic flirtation, splicing the focal depths of two people talking through screens and mirrors. Slightly douchey “you asleep?” texts give an inventive camera view to an all-too-relatable panic before a text reply. Misinterpreted Google translate results turn into daggers that pierce the heart. Park’s off-kilter filmic gestures feed into the rhythm of Decision to Leave’s precise dance, and as his cinematic language comes to full circle, we are left devastated by the universal language of longing as we wait for the waves to clear up.

—

2. Women talking

Women Talking begins with an opening text “What follows is an act of female imagination.” A thought experiment of a film, Women Talking finds itself walking the fine line between allegorical and literal as it contemplates the future of a group of Mennonite women who have found themselves in a constant state of male abuse. On a rare day when the men of the community are away, trying to post bail for the man who got caught enacting the abuse no less, the women find themselves in a fraught debate whether they should fight against the abuse, or pack up and leave.

Perhaps a product of its thought-experiment structure, Polley weaves a conversation of ideas that feels impossible, maybe even too theoretical and theatrical for some. Heavy in its content and forceful in its rhetoric, we observe a space in which women try to come to terms with their own words, actions, and memory or lack thereof. Yet, equal measure gives way to smoke breaks or young girls playfully braiding their hair to stave off boredom. Polley even ventures outside the conversation within, letting her camera roam beyond the text, trailing children at their moments of play and bliss, documenting an untouched innocence. Small glimmers of saturation breathe life and hope into the world compared to the bleak cinematography that accurately reflects their situation. In her filmmaking and structure, Polley finds a fluid language in visualizing the emotional process. Understanding that this process is an expanse of weighty words, spaces once occupied, memories of loved ones, smoke breaks, The Monkees, and so much more, all interweaving against one another into a chain reaction blur.

In writing about Women Talking, I think back to a quote Polley gave for the New Yorker about sexual assault, “When someone gets into a car accident, if you asked them all the details…you wouldn’t expect them to remember all of that. But we do somehow expect the survivors of sexual assault to remember all these details. It’s a complete misunderstanding of what’s going on in someone’s brain, and the inability to consign things to memory, in that moment after trauma.” Discussion on trauma will never satisfy everyone's expected talking points. How can we have a proper and meaningful conversation and reform on violence and abuse when we do not give victims the necessary tools or space to reconcile their abuse from a greater system? I am not sure there is an answer beyond “we cannot.” But to have a document that posits a world that makes space for the emotional processing of trauma, that gives way to the simple act of talking, whether about the theoretically impossible or the “moment not consigned to memory,” is what makes Women Talking all the more paramount.

——

1. Aftersun

Towards the end of the film, after a long day in Turkish ruins, father and daughter Calum (Paul Mescal) and Sophie (Frankie Corio), amid a dinner reminiscing the day, take a photo to celebrate. As their conversation continues, director Charlotte Wells fixates her camera on the polaroid, observing it develop into a foggy haze of an image, clear enough to see the final product but sorely missing depth, context, or focus. An apt metaphor for what Wells is searching for in her directorial debut, Aftersun beautifully explores memory against the truth with an incredible touch of empathy and self-reflexivity as Wells slowly tries to fill in the holes of her father she supposedly once knew. On the outside, Calum and Sophie seem to be having a decent holiday. Carelessly swimming in the pool and hanging out with the “cool kids,” Sophie’s days fill with delight. But, Wells's observations on Calum question the statement of a decent holiday as the camera holds itself long enough to document the unnoticed. Finding Calum lying alone on a costly rug, processing the crystallization of his toothpaste spit in a lonely room, catching a sneaky smoke session, or hearing an off-hand anecdote of potentially not making it to his 40s, we discover an incomplete portrait of a man. A man with a mysteriously silent sadness and anger, potentially repressing the need to call for help.

In the beginning, camcorder footage shows Sophie asking Calum where he thought he would be now. The footage cuts and we observe the rest of their holiday. We return to this moment midway through the film. When the scene continues beyond the beginning camcorder footage, it breaks out of the initial camcorder frame and frames the rest of the scene through a blank TV reflection with a sliver of a mirror reflection on the side. Similar to the polaroid, it captivatingly projects the idea of ephemerality, the fractured nature of memory, and its imperfections in deciphering the truth. The confidence to build upon these intimate moments, all leading to one of the most devastating needle drops of the year, with the filmmaking flourish and precision of an established auteur makes Aftersun the miracle it is. It is difficult to imagine the suffering of those who raised us. We convince ourselves to view our parents as invincible. Aftersun provides us with a new understanding of the memory of our parents and memory in general, waiting for the same camcorder initially used to excavate the “truth” to complete a full 360-pan and transport us to a new space. A space where the past and present can finally see each other with a bit more clarity and have that one last dance.

—